Programación orientada a objetos en Arduino

09 Mar 2022

¿Has tenido que volver a un sketch desarrollado para Arduino y tuviste que pasar un buen rato intentando entender qué fue lo que hiciste en su momento? En este post pretendo aplicar conceptos de la programación orientada a objetos a sketchs para Arduino y validar si el código resultante es más fácil de mantener. Spoiler alert: sí, el código resultante es más fácil de mantener y va a ahorrarte tiempo a la hora de mantener tu código.

En muchos tutoriales y ejemplos de código C++ para Arduino se puede observar este patrón: el código generalmente se encuentra en un solo archivo .ino que contiene todo o casi todo el programa, con excepción de algunas librerías de terceros, que son invocadas desde el sketch.

Si necesitamos volver a revisar un programa, tras un cierto tiempo, para corregir algo o añadir alguna nueva funcionalidad, pueda que nos lleve un buen rato el volver a entender la lógica del código. Lo mismo sucede si alguien más va a revisar nuestro programa o si nosotros vamos a mantener el código de alguien más.

En este post, intentaré refactorizar algunos programas para Arduino, reescribiendo el código bajo el paradigma de la programación orientada a objetos (POO), con la intención de organizar el código de manera conceptual. La idea es que el programa resultante tenga la misma funcionalidad que el original y se pueda mantener con relativa facilidad, de modo que cuando volvamos a revisarlo, nos lleve menos tiempo el comprender la lógica de nuestro dispositivo.

Preliminares

Este artículo asume que, además de Arduino, conoces los conceptos de la programación orientada a objetos. Si tienes alguna duda al respecto, o si ves algún error o imprecisión, estaré agradecido si me dejas un comentario.

POO con un ejemplo simple

Comencemos con el ejemplo Fading a LED, de la documentación de Arduino. En este ejemplo, el dispositivo tiene conectado un led cuyo brillo va de 0, es decir el led está apagado, hasta 255, su punto de mayor brillo. A partir de ese punto, comienza a disminuir el brillo hasta llegar a apagarse. Luego repite el ciclo nuevamente. Este es el código que sale en la documentación:

/*

Fade

This example shows how to fade an LED on pin 9 using the analogWrite()

function.

The analogWrite() function uses PWM, so if you want to change the pin you're

using, be sure to use another PWM capable pin. On most Arduino, the PWM pins

are identified with a "~" sign, like ~3, ~5, ~6, ~9, ~10 and ~11.

This example code is in the public domain.

https://www.arduino.cc/en/Tutorial/BuiltInExamples/Fade

*/

int led = 9; // the PWM pin the LED is attached to

int brightness = 0; // how bright the LED is

int fadeAmount = 5; // how many points to fade the LED by

// the setup routine runs once when you press reset:

void setup()

{

// declare pin 9 to be an output:

pinMode(led, OUTPUT);

}

// the loop routine runs over and over again forever:

void loop()

{

// set the brightness of pin 9:

analogWrite(led, brightness);

// change the brightness for next time through the loop:

brightness = brightness + fadeAmount;

// reverse the direction of the fading at the ends of the fade:

if (brightness <= 0 || brightness >= 255) {

fadeAmount = -fadeAmount;

}

// wait for 30 milliseconds to see the dimming effect

delay(30);

}Si bien este sketch no es muy complejo, nos servirá como base para nuestro método de refactorización. Luego podremos abordar un ejemplo más complejo.

Para introducir conceptos de la programación orientada a objetos a este código, es preciso añadir una clase que represente nuestro led. En esa clase podremos encapsular la lógica del componente. Las variables led, brightness y fadeAmount del código original están conceptualmente relacionadas al propio led. Una representa el número de pin y las otras dos son el nivel de brillo y el valor que se incrementa en cada operación, respectivamente. Estos atributos constituyen la configuración de nuestro led y su estado en un determinado momento del tiempo.

Además del estado de nuestro led, están las acciones que vamos a requerir que sean ejecutadas. Tanto el acto de indicarle al led que incremente o decremente su brillo, así como el revertir la dirección del proceso (fade in, fade out), le serán comunicados a nuestro objeto led a través de los métodos que vamos a estipular para nuestra clase.

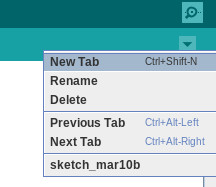

Para crear la clase que representa al led, en el IDE de Arduino, añadiremos un nuevo archivo a nuestro sketch. Para ello, vamos a abrir una nueva pestaña para nuestro archivo FadingLed.h:

En ella pondremos la declaración de la clase:

#ifndef FADING_LED_H

#define FADING_LED_H

class FadingLed {

int pin, brightness, fadeAmount{5};

public:

FadingLed(int);

void setup();

void applyNextFadeStep();

void reverseFadingAtEnds();

};

#endifLas dos primeras líneas y la última constituyen la definición de guardas para evitar errores del compilador cuando el archivo FadingLed.h es incluído más de una vez en el código de la aplicaición.

A continuación vamos a definir los métodos de la clase, añadiendo una nueva pestaña con el nombre FadingLed.cpp.

#include <Arduino.h>

#include "FadingLed.h"

FadingLed::FadingLed(int p)

{

pin = p;

}

void FadingLed::setup()

{

pinMode(pin, OUTPUT);

}

void FadingLed::applyNextFadeStep()

{

brightness = brightness + fadeAmount;

analogWrite(pin, brightness);

}

void FadingLed::reverseFadingAtEnds()

{

if (brightness <= 0 || brightness >= 255) {

fadeAmount = -fadeAmount;

}

}La línea donde incluimos el archivo Arduino.h es para que el compilador sepa encontrar la definición de los métodos pinMode y analogWrite. Esto puede considerarse un code smell, ya que nuestra clase está fuertemente acoplada a Arduino. Si quisiéramos llevarnos este código a otra plataforma donde también tengamos un led, tendríamos que migrar bastante código para adaptar nuestras clases. Existen soluciones para desacoplar nuestro programa de Arduino, como la inyección de dependencias, pero exceden el propósito de este post.

Ahora que hemos añadido el código para que la clase FadingLed sea funcional, ya podemos utilizarla desde nuestro sketch:

#include "FadingLed.h"

FadingLed led{9};

void setup()

{

led.setup();

}

void loop()

{

led.applyNextFadeStep();

led.reverseFadingAtEnds();

delay(30);

}Como se puede ver, el código principal del sketch ha quedado bastante más conciso. La comunicación con el objeto led a través de sus métodos deja explícita la intención, lo cual aumenta la legibilidad del código y facilitará la comprensión del programa por parte de algún colega que intente trabajar con nuestro programa o incluso nos ayudará a nosotros mismos a recordar de qué se trataba el código si volvemos a él tras un cierto tiempo.

Si el dispositivo Arduino incluyese más componentes (otros leds con otra lógica, sensores, etc), el beneficio del código estructurado sería aún más evidente, como veremos a continuación.

POO con un ejemplo más complejo

Veamos un ejemplo más complejo, en donde, al tutorial original Fading a LED, lo fusionamos con el tutorial Debounce on a Pushbutton de modo tal que, nuestro Arduino comience variando el brillo del led, como en el primer ejemplo del post, pero cuando pulsemos el botón, haremos que se detenga el proceso. Y al pulsar nuevamente el botón, resumiremos la secuencia de fade desde se quedó antes.

int led = 9; // the PWM pin the LED is attached to

int brightness = 0; // how bright the LED is

int fadeAmount = 5; // how many points to fade the LED by

const int buttonPin = 2; // the number of the pushbutton pin

int buttonState; // the current reading from the input pin

int lastButtonState = LOW; // the previous reading from the input pin

bool fading = true; // if the led is fading or not

// the following variables are unsigned longs because the time, measured in

// milliseconds, will quickly become a bigger number than can be stored in an int.

unsigned long lastDebounceTime = 0; // the last time the output pin was toggled

unsigned long debounceDelay = 60; // the debounce time; increase if the output flickers

// the setup routine runs once when you press reset:

void setup()

{

// declare pin 9 to be an output:

pinMode(led, OUTPUT);

pinMode(buttonPin, INPUT);

}

// the loop routine runs over and over again forever:

void loop()

{

// read the state of the switch into a local variable:

int reading = digitalRead(buttonPin);

// check to see if you just pressed the button

// (i.e. the input went from LOW to HIGH), and you've waited long enough

// since the last press to ignore any noise:

// If the switch changed, due to noise or pressing:

if (reading != lastButtonState) {

// reset the debouncing timer

lastDebounceTime = millis();

}

if ((millis() - lastDebounceTime) > debounceDelay) {

// whatever the reading is at, it's been there for longer than the debounce

// delay, so take it as the actual current state:

// if the button state has changed:

if (reading != buttonState) {

buttonState = reading;

// only toggle the LED if the new button state is HIGH

if (buttonState == HIGH) {

fading = !fading;

}

}

}

if (fading) {

// set the brightness of pin 9:

analogWrite(led, brightness);

// change the brightness for next time through the loop:

brightness = brightness + fadeAmount;

// reverse the direction of the fading at the ends of the fade:

if (brightness <= 0 || brightness >= 255) {

fadeAmount = -fadeAmount;

}

// wait for 30 milliseconds to see the dimming effect

delay(30);

}

// save the reading. Next time through the loop, it'll be the lastButtonState:

lastButtonState = reading;

}Podemos ver que el código para el debouncing se termina entremezclando con el código del fading. En estas condiciones, se empieza a dificultar la comprensión del programa. Esto es aún mas evidente si el dispositivo tiene más componentes.

Como ya disponemos de la clase FadingLed, creada para el ejemplo anterior, vamos a copiar los archivos FadingLed.h y FadingLed.cpp del ejemplo anterior a la carpeta de nuestro nuevo sketch para comenzar a refactorizar el programa principal:

#include "FadingLed.h"

FadingLed led{9};

const int buttonPin = 2; // the number of the pushbutton pin

int buttonState; // the current reading from the input pin

int lastButtonState = LOW; // the previous reading from the input pin

bool fading = true; // if the led is fading or not

// the following variables are unsigned longs because the time, measured in

// milliseconds, will quickly become a bigger number than can be stored in an int.

unsigned long lastDebounceTime = 0; // the last time the output pin was toggled

unsigned long debounceDelay = 60; // the debounce time; increase if the output flickers

// the setup routine runs once when you press reset:

void setup()

{

led.setup();

pinMode(buttonPin, INPUT);

}

// the loop routine runs over and over again forever:

void loop()

{

// read the state of the switch into a local variable:

int reading = digitalRead(buttonPin);

// check to see if you just pressed the button

// (i.e. the input went from LOW to HIGH), and you've waited long enough

// since the last press to ignore any noise:

// If the switch changed, due to noise or pressing:

if (reading != lastButtonState) {

// reset the debouncing timer

lastDebounceTime = millis();

}

if ((millis() - lastDebounceTime) > debounceDelay) {

// whatever the reading is at, it's been there for longer than the debounce

// delay, so take it as the actual current state:

// if the button state has changed:

if (reading != buttonState) {

buttonState = reading;

// only toggle the LED if the new button state is HIGH

if (buttonState == HIGH) {

fading = !fading;

}

}

}

if (fading) {

led.applyNextFadeStep();

led.reverseFadingAtEnds();

// wait for 30 milliseconds to see the dimming effect

delay(30);

}

// save the reading. Next time through the loop, it'll be the lastButtonState:

lastButtonState = reading;

}El próximo paso será agrupar, bajo otra clase, el código que encapsula el comportamiento de nuestro botón. Llamaremos a esta nueva clase DebouncedButton y la definiremos en el archivo DebouncedButton.h:

#ifndef DEBOUNCED_BUTTON_H

#define DEBOUNCED_BUTTON_H

class DebouncedButton {

int pin;

int buttonState; // the current reading from the input pin

int lastButtonState = LOW; // the previous reading from the input pin

// the following variables are unsigned longs because the time, measured in

// milliseconds, will quickly become a bigger number than can be stored in an int.

unsigned long lastDebounceTime; // the last time the output pin was toggled

unsigned long debounceDelay{50}; // the debounce time; increase if the output flickers

public:

DebouncedButton(int);

void setup();

bool wasPressed();

};

#endifLuego en el archivo DebouncedButton.cpp ponemos la definición de los métodos de la clase:

#include <Arduino.h>

#include "DebouncedButton.h"

DebouncedButton::DebouncedButton(int p)

{

pin = p;

}

void DebouncedButton::setup()

{

pinMode(pin, INPUT);

}

bool DebouncedButton::wasPressed()

{

// read the state of the switch into a local variable:

int reading = digitalRead(pin);

// check to see if you just pressed the button

// (i.e. the input went from LOW to HIGH), and you've waited long enough

// since the last press to ignore any noise:

// If the switch changed, due to noise or pressing:

if (reading != lastButtonState) {

// reset the debouncing timer

lastDebounceTime = millis();

// save the reading. Next time through the loop, it'll be the lastButtonState:

lastButtonState = reading;

}

if ((millis() - lastDebounceTime) > debounceDelay) {

// whatever the reading is at, it's been there for longer than the debounce

// delay, so take it as the actual current state:

// if the button state has changed:

if (reading != buttonState) {

buttonState = reading;

// only toggle the LED if the new button state is HIGH

if (buttonState == HIGH) {

return true;

}

}

}

return false;

}Estamos listos para reescribir el sketch, valiéndonos de nuestra nueva clase:

#include "DebouncedButton.h"

#include "FadingLed.h"

DebouncedButton button{2};

FadingLed led{9};

bool fading = true; // if the led is fading or not

void setup()

{

button.setup();

led.setup();

}

void loop()

{

if (button.wasPressed()) {

fading = !fading;

}

if (fading) {

led.applyNextFadeStep();

led.reverseFadingAtEnds();

// wait for 30 milliseconds to see the dimming effect

delay(30);

}

}En este ejemplo es más notorio el beneficio de haber introducido clases que estructuren nuestro programa de manera conceptual. A mayor complejidad, mejor será el tener el código organizado. Adicionalmente, esto nos abre la puerta a otras buenas prácticas como lo son el añadir pruebas unitarias e inyección de dependencias que nos permitirán separar más aún la lógica de nuestros componentes de su implementación.

Eso es todo, por ahora. Espero el contenido les resulte útil de cara a experimentar con la estructuración de sketchs de Arduino. ¡Feliz refactorización!

¡Tu mensaje fue recibido! Una vez que sea aprobado, estará visible para los demás visitantes.

Cerrar